Recent Work

A catastrophic flood severs a mountain town from the rest of the world, threatening lives, and testing the bonds of family, love, and friendship. River in the House, a collection of linked short stories, now looking for a publisher, tells the story of a beautiful place in ruins and the triumphs of community and ingenuity, narrated in the distinct voices of residents of Brewster, Vermont. A family is haunted by a long-ago drowning: Rosa, a forester anxious to prove herself independent of men; Zed, her estranged brother, a museum guard whose wife has disappeared; and Clayton, their father, a Rhodes scholar who stokes the boiler in a plywood factory. Their neighbor, surrogate mother, Mikey Arbiteau gives birth at the worst possible time, drawing a Marine Veteran with PTSD into her dreams and deceits. Mikey’s only friend Ashley, in hiding from her husband when the storm hits, unearths dreadful compromises made by the people who raised her and understands what she has to do. A teacher, watching his son don snorkel and mask as the flood fills their home, discovers the truest lesson of parenthood.

Some of the stories from River in the House may be found in print issues of Epiphany, and Fifth Wednesday Journal guest edited by Alice Mattison, and can be accessed in online issues of Four Way Review, Harvard Review, and Waxwing Magazine.

From a personal essay, included in Solstice, “My mother’s Valentine”

“We are at a party at the Hoffmans’ house. I swing out over a cliff on a long-roped swing. My dress flutters in the sudden wind. My mother has made our mother-daughter dresses. The rest of the kids wear jeans. The mothers fuss over lemonade and hamburgers in the kitchen. As the afternoon wears on, and more people arrive, Gabe sets up a tape player out on the grass. Maybe everyone is supposed to dance, but only one does. In the center of a circle of clapping, hooting men, Dad performs a solo, arms in the air, hips swiveling, while he balances a bottle of vodka upright in his teeth. The music thumps and builds. He chugs the vodka and gyrates. The men stamp and whistle. I sneak peeks from my swing and feel the sickening thrill of the ground falling away below me.” Read more

Purchase Options:

- Your local bookstore

- Indiebound

- Amazon

- Random House

- Barnes and Noble

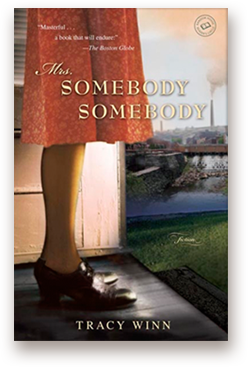

Mrs. Somebody Somebody

Funny, sad, and revelatory, the linked stories in Tracy Winn’s debut collection, Mrs. Somebody Somebody intersect in surprising ways to create a portrait of life in a mill town. Winn draws us into Lowell, Massachusetts, where her unforgettable characters are down on their luck, but making the most of it. In 1948, the man-crazy young mill worker of the title story forms an unexpected friendship with a mysterious co-worker; in 2004, a plucky immigrant child finds faith that her sister will return safely from Iraq; and in a story that bridges the time between, a secretive old bookie has reason to hide a fragment of bone in his pocket. Connecting all is the Burroughs family, whose stately home holds years of unspoken compromise and regret. In clean, sensuous prose, Winn delivers the truths of our experience, and illuminates the grace that connects us all. Read excerpt

Mrs. Somebody Somebody won the Sherwood Anderson Foundation award and was recognized as a finalist in fiction for the John Gardner Book Award, the Julia Ward Howe Award, and the Massachusetts Book Award.

Mrs. Somebody Somebody | Endorsements and Reviews

“A stunning patchwork of American life” —Vogue

“In Mrs. Somebody Somebody, Tracy Winn uses her substantial powers of language and observation to explore the ties that bind and the secrets that separate. Like the Merrimack River that flows through them, these wonderful stories run deep.” —Elizabeth Graver, author of Kantika, Awake, The Honey Thief, and Unravelling

“You won’t easily forget these characters, mill owners and union organizers, hair dressers and immigrants, whose lives are full of loss and discovery, regret and beauty, and whose stories brush against one another, overlap, and intersect in unexpected ways. These are deeply satisfying stories, subtle, intelligent, and beautifully crafted.” —Kim Edwards, author of The Memory Keeper’s Daughter

“Short stories may not attract the sort of attention that novels or memoirs do today, but Winn’s masterful debut serves as an affirmation of their emotional potency. With little fanfare, she has produced a book that will endure.” —Steve Almond, Boston Globe, author of All the Secrets of the World, and Rock and Roll Will Save Your Life

“It’s with extraordinary grace and subtlety that Tracy Winn crafts the interconnected stories that make up Mrs. Somebody Somebody. We’re immersed here in varied and individual lives, but these stories as a whole tell an insightful and historically sweeping tale of labor and class in modern America. To achieve that kind of scope while rendering the smallest gestures and exchanges of dialogue with such acuity is more than remarkable—it’s inspiring. When characters are brought to life with this vibrant nuance, they continue to live far beyond the page.” —Thisbe Nissen, author of How Other People Make Love, Osprey Island, and The Good People of New York

A rare achievement, Tracy Winn’s characters struggle with unexpected losses and damaging habits, rarely triumphing over the troubles that fill their lives, but always questioning the hard truths that hold them in place. —Atlantic Monthly

“Even at age 80 I am doing something new: reading for the second time {these] stories which first moved me deeply only a couple of months ago…It’s like the enjoyment that comes with savoring a repeat performance of a great string quartet.” —A reader